Posted on 22/02/13 by Harpreet Singh | Category: Camps Press

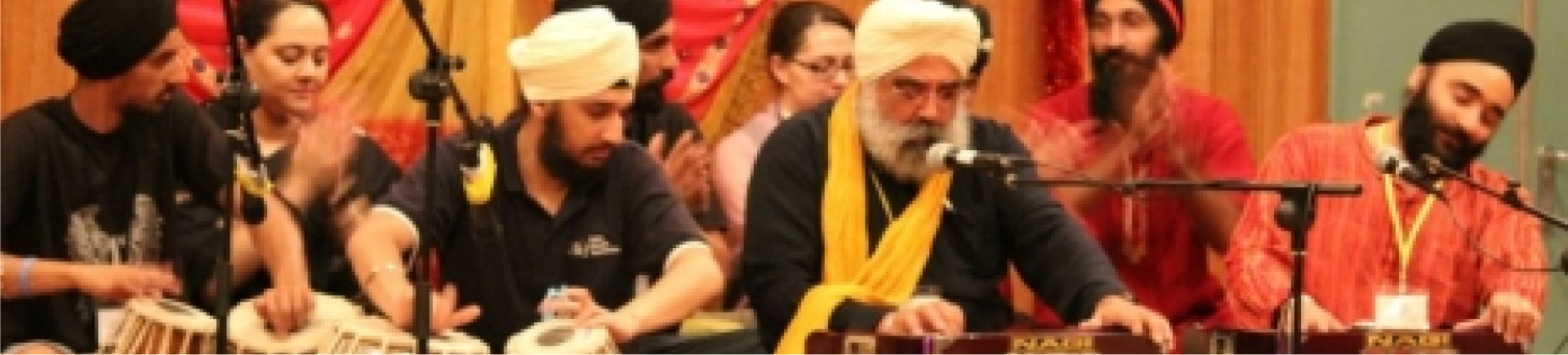

Joyful Noise; Dya Singh, the Sikh Minstrel on the World Music Stage

ROSALIA SCALIA

Dya Singh knows how to make a joyful noise unto the Lord.

And in that way, his music provides listeners with an uplifting entertainment that brings his audiences closer to God, though they may not always realize it.

“My main music is kirtan – whether in concert or in a gurdwara. The difference is in a gurdwara, the Guru (Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh Scripture) takes center stage. Imagine a king sitting in: hence the kirtan is directed towards the king. But in an ‘entertainment’ concert, the Guru Granth is absent in physical form. The focus shifts to the singing. I direct my group members and the kirtan becomes couched as ‘entertainment’ – albeit, of a spiritual kind,” says Dya, who agreed to an interview on a dreary Sunday morning in Melbourne.

Known worldwide as the most significant singer/musician of the Sikh mystical musical tradition and as one of Australia’s pioneers in the world music genre, Dya has incorporated an array of instruments from around the world into the performances of his renditions of the Sikh shabads and gurbani, and, as a result, his music has attracted fans from many faiths and walks of life to his performances

He and his musical group have performed at various arts festivals around the world, including in the US, Canada, England, Germany, Ireland, Japan, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, among others.

Originally from Malaysia and the son of a renowned Sikh spiritual minstrel, Giani Harchand Singh Bassian, Dya began learning as a child how to sing kirtan.

“I never had to realize that I had the gift of music. It was always with me since I was born or gained consciousness – at about 4 years old. My father was a ‘kirtanyia’ – the closest translation of that is ‘Sikh spiritual minstrel’, an interpreter of gurbani (Sikh scriptural hymns) in traditional strains of music hailing from Punjab and other regions of the subcontinent — folk, semi-classical and classical,” he says.

His musical training did not end with voice. He also learned tabla, playing “to improve my grasp of the intricate rhythm patterns that we have.”

He dabbled in sitar, but his forte is his rendition of shabads with different genres and traditions of music. And though his music incorporates the famous interplays between vocals, harmonium, which he also plays, and tabla, they happen with less frequency than with other singers, “like [the late] Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, etc., because the main thrust is the union of music with voice as a vehicle to bring out the essence of the spiritual message of the shabad. Interplays and other raag musical ‘acrobatics’ have their moments, especially in concerts, but very much less in the gurdwara because they can take one away from the core message which needs to be relayed,” he says.

His musical training coupled with his lifelong practice of it and his keen understanding of the raags — the vehicle to present the shabads — has enabled him to compose his own renditions as much as possible in a music form that allows, nay, encourages and emphasizes improvisation.

“I compose most of my renditions. I do retain some classics in kirtan which never die. Notations are minimal because I use the raag system, in which the melody just flows after it has been composed using a raag base – something I was born with. I use the raag notation system which I have developed from my father’s style,” Dya explains, also noting like a true musician that he takes great joy in incorporating musical instruments and styles from other cultures.

Not everyone has accepted his non-traditional and culturally inclusive way of performing the shabads.

“I faced a fair degree of opposition and non-acceptance by some traditional Sikhs. Where I was perhaps a sensation and a breath of fresh air for Sikh youths and the major part of the Sikh population, as well as the non-Sikh world, I faced ridicule from traditionalists.

“Kirtan has hitherto been limited to gurdwaras or homes. I took it to concert stages. Kirtan is traditionally done with mellow accompaniment of mainly stringed instruments. I had electric guitars, didgeridoos, and other ‘unknown’ instruments. Kirtan is normally laid back – our renditions can be in the face and loud sometimes. Kirtan is to curb passions, our renditions can stir passions! Kirtan must be done and listened to with heads covered, in somber and meditative surroundings, preferably with people sitting on the floor, cross-legged, bare-footed of course, with heads covered, and in silence. Our renditions in concerts have people sitting on chairs with footwear on, heads uncovered, sometimes bare bodied, with some up dancing, clapping … it generally can get fairly celebratory, noisy, even rowdy, in music festivals.

“So, you can imagine the flak that I copped! But as time went on and the traditionalists realized that at least their younger generations, many of whom had little time for kirtan, were happy to play our music albums at home and on their iPods. The opposition slowly fell away.”

Still, Dya has been denied the stage in some conservative gurdwaras worldwide, and he was refused time to do kirtan at the Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple in Amritsar) because some members of his musical group are not Sikhs. Protocol at the Golden Temple is that only amritdhari Sikhs can do kirtan there, which disqualifies the non-Sikh members of his musical group.

“I was asked to do kirtan with other Sikh musicians but refused because my colleagues accompany me around the world to do kirtan, and I cannot abandon them even if it means I miss out on the opportunity to do service in the Darbar Sahib,” he says.

More than that, Dya notes that the Darbar Sahib today, under the influence of encroaching Hindu practices, does not allow — against the very principles of Sikhi — women to sing in the inner sanctum sanctorum.

“My daughters too were not being allowed to sing with me in the Harmandar. I am a strong advocate of women being allowed to sing at Darbar Sahib. The practice of not allowing women to sing there, or to do seva of washing the floors of the inner sanctum, are all contrary to Sikh ideology. I can accept non-Sikhs from not performing there – even though that too is contrary to the teachings and practices of our Gurus – but I cannot accept women not being allowed to sing or do seva at Darbar Sahib,” he says.

While making his joyful noise seems like a no brainer and a divine calling, for this gifted artist, being a musician was not always a priority.

He stopped singing publicly, and after a 15-year hiatus found his way back to the music, presenting concerts in Australia in 1992 and then fully devoting himself to developing a musical career and becoming a full-time musician in 1995.

“I was pre-occupied with my other career — as an accountant — with marriage, and raising a family, and except for singing the odd shabad at the gurdwara, music then was not my priority. I was trying to be a success in my profession – music not being considered a profession.

“Ironically, though, if there is one word to describe Sikhism, it would be ‘music’ because our Gurus were strong proponents of it.”

Dya found himself dutifully “beavering away as an accountant,” after having migrated to Adelaide, Australia, to support and raise his three daughters when the world changed, when 1984 happened.

“I became disillusioned because of the attack on the Sikh psyche. I yearned to do something meaningful.”

Dya moved away from being an accountant towards administration and management, and found himself beginning a course in Management with the Australian Institute of Management.

“The final dissertation required doing a Business Plan to float a viable product into the market. My supervisor had seen me do kirtan in the Adelaide gurdwara and suggested that I do a business plan to float kirtan as a mainstream product. Well, the long and short of it is that my business plan did not get me an ‘Honours’ but the critical remark of the adjudging panel was that this idea was so crazy that it might just succeed! I am still following that business plan because it was the impetus I needed to head in this direction. Life has been more fulfilling though those nearest and dearest to me thought I’d gone crazy.”

Dya does not focus his career solely on performance, touring, and releasing CDs. He also conducts workshops and teaches individual classes on sound meditation and his special brand of vocal training. He performs conventional kirtan in the traditional Sikh style and facilitates worldwide Sikh Youth Camps, interacting with students in primary and secondary schools, teaching cultural education and awareness.

“Dya has a unique style of inspiring our youths to learn and play music/kirtan, “ says Satwant Singh Calais, a sevadar at the Sikh Youth Australia. “We have seen some amazing results with our youth who have hitherto shown no inclination to learn musical instruments and within a few years learn how to do kirtan and come and present their shabads in our camps.”

He notes that Dya is a co-founder of the camps and has dedicated more than 15 years of his service to Sikh-Aussie youth.

“Parents come away in tears when they see their children take up and have the confidence to do kirtan in front of 300 people while at home they are not that way inclined.”

Dya’s musical group expanded both in sound and in number, including the addition of Keith Preston as a manager and musician, and landed gigs in prestigious arts festivals and garnered raving reviews.

“The group was built on friendship and tolerance in the first place of people sharing music and being friends and supporting each other to explore spirituality hrough music,” says Preston of the Migrant Resource Centre of South Australia. “Dya was definitely the leader of the group and it was ‘his’ music that was being played so musicians had to be comfortable supporting his quest. Dya was very open about working with musicians of any kind as long as they had the right kind of personality, values and approach to improvised playing within the framework of Sikh music.”

Performances, glowing reviews and an ever growing popularity of devoted fans aside, Dya also conducts weekend retreats in self-awareness, visualization, and meditation techniques and often finds himself representing the Sikh faith in interfaith forums, events, prayer meetings and talks.

In short, through his music, Dya has become an ambassador of Sikhi.

“The immediate feeling you get with Dya Singh is that he remains untouched by fame. When you meet him with a hug you get the feeling that you have known him forever. His humility touches everyone. If you ask him to sing a shabad or Guru’s song, he bursts forth immediately without making a lame claim that his throat is paining,” says Sangat Singh, a retired plantation manager in Malaysia who has known Daya since his youth.

“In a global village setting, we have no choice but to keep introducing new sounds into our traditional music but I always urge youth to learn the traditional music and then strive forth and reach out to other cultures and music,” Dya says. “My whole quest, in introducing world music to kirtan and kirtan to world music, has been to fire the imagination of our younger generations of Sikhs towards Sikhism as a way of life — our music, kirtan, being a major part of it. The only aspect that holds Sikhs together is Sikhism itself, and Sikh music is part of that international Sikh identity.”